Tau protein: Physiological functions and multifaceted roles in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders

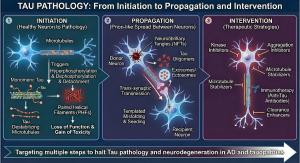

Tau pathology: From initiation to propagation and therapeutic intervention. This schematic depicts the three-stage cascade of tau pathology and corresponding therapeutic strategies: Initiation, Propagation and Intervention.

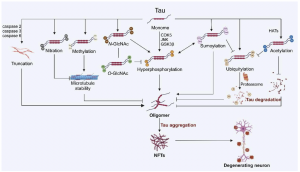

The cross-talk between tau’s PTMs. Hyperphosphorylation of tau can be catalyzed by multiple enzymes, including CDK5, JNK, and tau phosphorylation cross-talks with glycosylation and sumoylation.

Four decades of tau research reveal a protein essential for brain health that also drives Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and psychiatric disorders when it goes wrong

But tau has a dark side. When this essential protein malfunctions, it transforms into one of the most destructive forces in the human brain, forming the tangled masses that define Alzheimer's disease and contribute to Parkinson's, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and a growing list of psychiatric conditions.

A comprehensive Thought Leaders Invited Review published today in Genomic Psychiatry presents what may be the most complete picture yet assembled of tau protein and its remarkable dual nature. Dr. Peng Lei of Sichuan University and colleagues have synthesized more than 300 studies spanning over four decades of research. What emerges from their analysis fundamentally changes how scientists and physicians should think about brain diseases.

"Our review highlights that tau's role extends far beyond Alzheimer's disease," said Dr. Lei. "Understanding how this protein functions in health and how it malfunctions in disease opens new avenues for diagnosis and treatment across multiple neurological and psychiatric conditions."

The Protein That Keeps Neurons Running: Tau was discovered in the 1970s almost by accident. Researchers studying the internal skeleton of cells, the network of tiny tubes called microtubules that give cells their shape and serve as highways for transporting materials, noticed a protein that always seemed to show up with the building blocks of those tubes. They named it tau, from the Greek letter, and for years assumed its job was simple: help hold the microtubules together.

That assumption was wrong. Spectacularly wrong.

The review traces how scientific understanding evolved from viewing tau as a passive structural element to recognizing it as an active participant in processes no one expected. Tau regulates how iron moves through neurons. It participates in the molecular machinery of learning and memory. It even influences how the pancreas releases insulin.

Consider the iron connection. Neurons need iron to function, but iron is also dangerous. Free iron generates toxic molecules called free radicals that damage cells. So the brain maintains iron levels with exquisite precision, and tau plays a crucial role in that balancing act.

Dr. Lei's previous research demonstrated that tau helps transport a protein called amyloid precursor protein, or APP, to the surface of neurons. Once there, APP stabilizes the molecular pumps that export iron out of cells. When tau is absent or dysfunctional, those pumps fail, and iron accumulates inside neurons.

The consequences are severe. In mice engineered to lack tau entirely, iron deposits appeared in the very brain regions that degenerate in Parkinson's disease. By twelve months of age, these mice had lost the dopamine-producing neurons of the substantia nigra, the same neurons that die in human Parkinson's patients.

This finding sent researchers back to examine human brain tissue with fresh eyes. What they found was striking: iron accumulation occurs precisely in the brain regions where soluble, functional tau levels drop. The pattern held across multiple diseases.

The Insulin Surprise. Perhaps no finding in the review is more unexpected than tau's role in insulin metabolism. Diabetes and dementia have long been linked in ways that puzzled researchers. People with type 2 diabetes face significantly elevated risk of developing Alzheimer's disease, but why? The answer may lie in tau.

In the brain, the absence of tau promotes insulin resistance in the hippocampus, the brain's memory center. But tau's influence extends beyond the brain. The protein is expressed in the pancreas, where insulin is produced, and it appears to regulate how pancreatic cells release that hormone.

When researchers eliminated tau function in diabetic mice, whether through genetic engineering or drugs, something remarkable happened: insulin secretion increased, blood sugar normalized, and the diabetic symptoms improved. Tau, it seems, normally suppresses insulin release.

This finding carries implications far beyond basic science. Type 2 diabetes affects more than 37 million Americans. If tau-targeting treatments could address both dementia risk and blood sugar control, the therapeutic potential would be enormous. But as the review makes clear, the relationship is complex. The same protein that causes trouble when it aggregates also performs essential functions that cells cannot live without.

When Good Proteins Go Bad. The 1980s changed everything scientists thought they knew about tau. Researchers examining the brains of Alzheimer's patients under electron microscopes discovered that the characteristic tangles found in diseased neurons were made of tau. Not foreign invaders. Not toxic chemicals. A normal brain protein, twisted into unrecognizable shapes.

The review provides a detailed accounting of how this transformation occurs. In healthy brains, tau maintains a phosphorylation level of about 2 to 3 phosphate groups per protein molecule. Phosphorylation is a chemical modification that cells use to control protein activity, like a molecular on-off switch. But in Alzheimer's disease, that ratio climbs to 5 to 9 phosphate groups per tau molecule, roughly a threefold increase.

This hyperphosphorylation changes tau's behavior completely. Normally, tau binds tightly to microtubules, keeping them stable. Hyperphosphorylated tau releases from the microtubules and floats free in the cell's interior. Once free, it begins to stick to other tau molecules. Small clumps form, then larger aggregates, then the tangled masses that pathologists recognize as neurofibrillary tangles.

But phosphorylation is only one way tau can be modified. The review catalogs an astonishing 95 distinct modifications at 88 different locations on the tau protein. Each modification alters tau's behavior in specific ways. Some promote aggregation. Others inhibit it. Some target tau for destruction by the cell's waste disposal systems. Others protect it from degradation.

The complexity is daunting, but it also offers hope. If scientists can identify which modifications drive disease, they might develop drugs that specifically target those harmful changes while leaving beneficial tau functions intact.

Tau Spreads Like an Infection. One of the most disturbing discoveries about tau pathology is that it spreads through the brain in a predictable pattern, almost like an infection moving from person to person, except in this case it moves from neuron to neuron.

In Alzheimer's disease, tau tangles typically appear first in the brainstem, particularly in a region called the locus coeruleus. From there, the pathology spreads to the transentorhinal and entorhinal cortex, then to the hippocampus, then to the amygdala and thalamus, and finally to the neocortex. This progression, mapped by the German neuropathologist Heiko Braak, is now known as Braak staging and is used worldwide to classify Alzheimer's severity at autopsy.

How does tau spread? The review examines current evidence and finds that pathological tau can be released from dying neurons, taken up by neighboring healthy neurons, and trigger those previously healthy cells to develop tangles of their own. The process involves tiny cellular packages called exosomes, specialized receptors on cell surfaces, and a poorly understood mechanism by which incoming tau "seeds" convert normal tau into the pathological form.

Researchers have demonstrated this spreading experimentally. When tau extracted from brains of mice with tauopathy is injected into healthy mouse brains, the healthy mice develop tau pathology. The pathology spreads from the injection site along the brain's network of neural connections.

Understanding this spreading mechanism matters enormously for treatment. If pathological tau can be intercepted before it spreads, perhaps the disease could be halted in its early stages.

The Psychiatric Connection. The review's most provocative sections examine tau's emerging connections to psychiatric disorders, a link that most physicians and patients have never heard about.

In patients with early-onset schizophrenia, plasma total tau levels are significantly lower than in healthy controls. Adult-onset schizophrenia patients show decreased serum levels of both total tau and phosphorylated tau. These findings raise questions that researchers are only beginning to address.

Delirium offers another window into tau's psychiatric role. Delirium is the sudden confusion and disorientation that often affects elderly patients after surgery or during serious illness. It is extremely common, affecting up to 50% of hospitalized older adults, and it dramatically worsens outcomes.

Recent studies have found that preoperative plasma levels of phosphorylated tau, particularly the form called p-tau217, predict which patients will develop postoperative delirium. The mechanism may involve anesthesia and surgery acutely elevating blood tau levels, with that tau then crossing into the brain and disrupting normal function.

For patients with Alzheimer's disease, neuropsychiatric symptoms including apathy, depression, anxiety, delusions, and hallucinations are common and devastating. The review presents evidence that these symptoms correlate with tau pathology. Patients with Alzheimer's disease who experience psychotic symptoms have significantly higher levels of phosphorylated tau in their frontal cortex. Tau PET imaging shows stronger tau signals in the amygdala and temporal cortices of patients with delusions or hallucinations.

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, the brain disease associated with repeated head impacts in athletes and military personnel, also manifests psychiatric symptoms before cognitive ones. Depression, impulsivity, aggression, and suicidal thoughts often appear years before memory problems. Postmortem studies show that these psychiatric symptoms correlate with tau accumulation in the frontal cortex.

The implications are significant. If tau accumulation in particular brain circuits directly produces psychiatric symptoms, then treating tau might treat those symptoms, a fundamentally different approach than current psychiatric medications.

The Biomarker Revolution. One of the most practically important sections of the review traces the development of tau as a disease biomarker. For decades, Alzheimer's disease could only be definitively diagnosed at autopsy. That changed with the development of tests that measure tau in cerebrospinal fluid and, more recently, in blood.

The story begins in the mid-1990s, when researchers first detected elevated tau levels in the cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer's patients. Since then, the field has advanced rapidly. Different phosphorylated forms of tau appear at different disease stages, potentially allowing doctors to track disease progression over time.

Phosphorylated tau at position 217, called p-tau217, has emerged as particularly useful. It can distinguish Alzheimer's disease from other forms of dementia with remarkable accuracy. In some studies, blood p-tau217 tests perform as well as cerebrospinal fluid tests, which require a spinal tap, or PET brain scans, which cost thousands of dollars.

Different tau species reflect different aspects of pathology. P-tau217 levels begin rising when amyloid plaques form. P-tau205 elevates when neuronal dysfunction begins. A form called MTBR-tau243, derived from the microtubule-binding region of tau, specifically reflects tangle burden as measured by PET imaging.

The clinical implications are substantial. Blood tests for tau could enable early detection of Alzheimer's disease, when treatments might be most effective. They could help doctors distinguish Alzheimer's from other causes of cognitive decline. They could monitor whether treatments are working. And they could identify research participants for clinical trials of new drugs.

Why Treatments Have Failed So Far. Despite impressive progress in understanding tau biology, the review authors note a sobering reality: no tau-targeting drug has demonstrated significant clinical efficacy. The reasons illuminate just how difficult treating brain diseases can be.

Several approaches have been tried. Antisense oligonucleotides, or ASOs, are engineered molecules that reduce tau production by interfering with its genetic instructions. One such drug, BIIB080, has shown promise in early trials, significantly reducing tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with mild Alzheimer's disease. But clinical trials take years, and the results are not yet available.

Drugs targeting the kinases that phosphorylate tau have produced mixed results. Lithium, the mood stabilizer used to treat bipolar disorder, inhibits GSK3, one of the main enzymes that phosphorylates tau. Short-term lithium treatment in Alzheimer's patients showed no benefit. But longer treatment (two years) improved outcomes in patients with mild cognitive impairment. The pattern suggests that kinase inhibition might work, but only with the right dose, timing, and patient population.

Immunotherapy, using antibodies to target and remove pathological tau, has been extensively studied. Multiple antibodies have completed clinical trials. None has shown efficacy in early Alzheimer's disease. Perhaps antibodies cannot reach tau inside cells, where most aggregation occurs. Perhaps they target the wrong forms of tau. Perhaps they are given too late in the disease process.

The blood-brain barrier presents another obstacle. Most drugs cannot cross from the bloodstream into the brain. Developing delivery systems that get therapeutic amounts of drug into the brain remains a major challenge.

New approaches offer hope. Researchers have developed molecules called PROTACs that hijack the cell's own waste disposal machinery to destroy tau. Others have engineered antibodies that can enter cells and target tau aggregates directly. Still others are exploring whether proteins in the TRIM family can be harnessed to clear pathological tau.

The Road Ahead. The review concludes by identifying critical gaps in current knowledge. We still do not fully understand how tau pathology begins, what triggers a healthy protein to start aggregating, or why some people develop tau pathology while others do not. The precise mechanisms by which tau spreads from neuron to neuron remain incompletely mapped. And the relationship between tau and psychiatric symptoms demands much more investigation.

Perhaps most importantly, researchers need to understand whether tau pathology is a primary driver of disease or a secondary consequence of other processes. This question has profound implications for treatment. If tau is the driver, then reducing tau should slow or stop disease. If tau aggregation is a downstream effect of something else, then targeting tau alone is not sufficient.

The review represents a synthesis of knowledge across neuroscience, psychiatry, and medicine. It provides researchers with a comprehensive framework for understanding tau biology. It offers clinicians a roadmap to emerging diagnostic tools. And it gives patients and families a clearer picture of where the science stands and where it is heading.

Tau research has come remarkably far in four decades. A protein once dismissed as a minor structural component has emerged as central to our understanding of how the brain ages, how it breaks down, and how it might someday be repaired.

About This Research: The Thought Leaders Invited Review is titled "Tau protein: Physiological functions and multifaceted roles in neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders." The corresponding author is Dr. Peng Lei, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China. The peer-reviewed article is freely available via Open Access, starting 16 December 2025 at: https://doi.org/10.61373/gp025i.0122

An accompanying editorial in Genomic Psychiatry provides additional perspectives. In "Tau's Two Faces: From Structural Scaffold to Pathological Destroyer," Editor-in-Chief Dr. Julio Licinio emphasizes the urgent need to translate four decades of accumulated knowledge into effective treatments. The editorial is freely available via Open Access, starting 16 December 2025 at: https://doi.org/10.61373/gp025d.0128

About Genomic Psychiatry: Genomic Psychiatry: Advancing Science from Genes to Society (ISSN: 2997-2388) represents a paradigm shift in genetics journals by interweaving advances in genomics and genetics with progress in all other areas of psychiatry. Genomic Psychiatry publishes peer-reviewed medical research articles of the highest quality from any area within the continuum that goes from genes and molecules to neuroscience, clinical psychiatry, and public health.

Visit the Genomic Press Virtual Library: https://issues.genomicpress.com/bookcase/gtvov/

Full website: https://genomicpress.com/

Ma-Li Wong

Genomic Press

mali.wong@genomicpress.com

Visit us on social media:

X

LinkedIn

Bluesky

Instagram

Facebook

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.